Americans have been betrayed. Sooner or later, Americans will realize that they have been led to defeat in a pointless war by political leaders who they inattentively trusted. They have been misinformed by a sycophantic corporate media too mindful of advertising revenues to risk reporting truths branded unpatriotic by the propagandistic slogan, “you are with us or against us.”

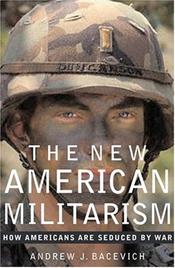

What happens when Americans wake up to their betrayal? It is too late to be rescued from catastrophe in Iraq, but perhaps if Americans can understand how such a grand mistake was made, they can avoid repeating it. In a forthcoming book from Oxford University Press, The New American Militarism, Andrew J. Bacevich writes that we can avoid future disasters by understanding how our doctrines went wrong and by returning to the precepts laid down by our Founding Fathers, men of infinitely more wisdom than those currently holding reins of power.

What happens when Americans wake up to their betrayal? It is too late to be rescued from catastrophe in Iraq, but perhaps if Americans can understand how such a grand mistake was made, they can avoid repeating it. In a forthcoming book from Oxford University Press, The New American Militarism, Andrew J. Bacevich writes that we can avoid future disasters by understanding how our doctrines went wrong and by returning to the precepts laid down by our Founding Fathers, men of infinitely more wisdom than those currently holding reins of power.

Bacevich, West Point graduate, Vietnam veteran, and soldier for 23 years, is a true conservative. He is an expert on U.S. military strategy and a professor at Boston University. He describes how civilian strategists – especially Albert Wohlstetter and Andrew Marshall – not military leaders, transformed a strategy of deterrence that regarded war as a last resort into a strategy of naked aggression. The resulting “marriage of a militaristic cast of mind with utopian ends” has “committed the United States to waging an open-ended war on a global scale.”

The greatest threat to the U.S. is not terrorists but the neoconservative belief, to which President Bush is firmly committed, that American security and well-being depend on U.S. global hegemony and impressing U.S. values on the rest of the world. This belief resonates with a patriotic public. Bacevich writes, “In the aftermath of a century filled to overflowing with evidence pointing to the limited utility of armed force and the dangers inherent in relying excessively on military power, the American people have persuaded themselves that their best prospect for safety and salvation lies with the sword.”

If Americans persist in these misconceptions, America will “share the fate of all those who in ages past have looked to war and military power to fulfill their destiny. We will rob future generations of their rightful inheritance. We will wreak havoc abroad. We will endanger our security at home. We will risk the forfeiture of all that we prize.”

Bacevich understands that the problem is not how to deal with terrorism but how to deal with the hubris, laden with catastrophe, that America is God’s instrument for bringing history to its predetermined destination. Being assigned such an exalted role creates the delusion that America’s virtue is unquestionable and its use of preemptive coercion is infallible, a delusion that led to the “cakewalk war” that would entrench democracy in the Middle East and have the troops home in 90 days.

American hubris, which flows so freely from President Bush’s mouth, explains why half the U.S. population yawns over the U.S. slaughter of Iraqi civilians and communist-style torture of Iraqi prisoners. The “cakewalk war” is now almost two years old and has claimed 10 percent of the U.S. occupation force as casualties. Yet, the delusion persists that the U.S. is prevailing in Iraq.

The new American militarism would be inconceivable, Bacevich writes, “were it not for the support offered by several tens of millions of evangelicals.” Books written about “militant Islam” could equally describe militant evangelical Christianity. How did a Christian doctrine of love and peace become an apology for war?

Bacevich explains that evangelicals, aghast at Vietnam era protests of America’s war against “godless communism,” turned to the military as the repository of traditional American virtues. For evangelicals, end-times doctrines converged eschatology with national security. Prophecies merged America’s fate with Israel’s. Islam inherited the role of godless communism and became the target of the war against evil. America emerged with the “same immensely elastic permission to use force previously accorded to Israel.”

America’s security and the well-being of the world are threatened by America’s unwarranted belief in the efficacy of force. War is ungovernable: “The shattered reputations of generals and statesmen who presumed to bring it under control litter the 20th century. On those rare occasions when war has yielded a seemingly decisive outcome, as in 1918 or 1945, it has done so only after exacting a staggering price from victor and vanquished alike. Even then, in resolving one set of problems, ‘good’ wars have fostered resentments or created temptations, leading as often as not to further conflict.”

The new American militarism has abandoned the Founding Fathers, deserted the Constitution, and unrestrained the executive. War is a first resort. Militarism is inconsistent with globalism and with American ideals. It will end in abject failure.

The world is a vast place. The U.S. has demonstrated that it cannot impose its will on a tiny part known as Iraq. American realism may yet reassert itself, dispel the fog of delusion, cleanse the body politic of the Jacobin spirit, and lead the world by good example. But this happy outcome will require regime change in the U.S.