Reprinted from Bracing Views with the author’s permission.

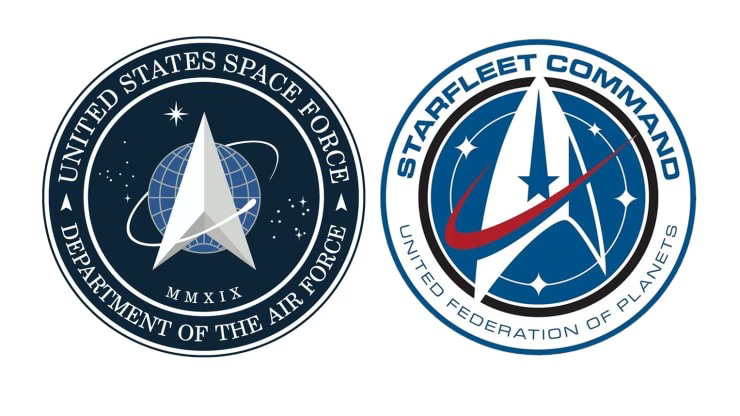

American exceptionalism and megalomania, combined with threat inflation, creates a toxic brew that drives trillion-dollar war budgets and global violence. I was reminded of this as I reread a review I wrote in 2009 about U.S. designs on space dominance. Ambitions to dominate space led to the creation of America’s “Space Force” by President Trump in 2019. I didn’t predict this, but note below the discussion of space visionaries within the Air Force who aspired to a new armed services branch dedicated to space dominance and exploitation. Indeed, the new service’s symbol took its inspiration from “Star Trek” insignia.

When it comes to “national security,” nothing succeeds like excess. Boldly go!

Anyway, here are a few thoughts from my review as written in 2009:

Did you know that in the 1950s and 1960s the U.S. military seriously considered building a base on the moon for nuclear-tipped missiles? In “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” William E. Burrows cites Air Force General Homer A. Boushey’s remark in January 1958 that:

The moon provides a retaliation base of unequaled advantage. If we had a base on the moon, the Soviets must launch an overwhelming nuclear attack toward the moon from Russia two to two-and-one-half days prior to attacking the continental U.S. – and such launchings could not escape detection – or Russia could attack the continental U.S. first, only inevitably to receive, from the moon—some 48 hours later—sure and massive destruction. (27)

Boushey’s vision of the moon as the ultimate U.S. nuclear missile site to safeguard and even to effectuate the policy of MAD, or mutually assured destruction, is only an extreme manifestation of the Air Force’s official policy to “dominate” the realm of space, “the ultimate high ground.” The belief that we had to arm the moon first, before the Soviets beat us to the lunar high ground, was driven “by the same combination of inadequate intelligence, paranoia, hubris, and consequent political over-reaction that got this country into the current quagmire in Iraq” (33), Burrows concludes.

Boushey may have been more bellicose than most, but consider this official proclamation – presented as an uncontestable truism – by General Lance Lord, Commander of Air Force Space Command, in 2006: “Space Superiority is the future of warfare. We cannot win a war without controlling the high ground, and the high ground is space.” (15) One might add a coda to Lord’s remark, to the effect that one may also lose a war while controlling, and even dominating, the “high ground” of space.

Space is most assuredly of vital importance to the United States. The U.S. relies on space for reconnaissance, surveillance, communication, intelligence, targeting, weather, and force application more than any other nation. U.S. exploitation of space enables its military goal of “global reach, global power.” In military jargon, U.S. assets in space are essential force multipliers.

That said, is space truly “the ultimate high ground,” as the U.S. military claims? Here, I think, analogies and metaphors mislead. Space is neither a ridge line to be seized and held, nor is it an “ocean” to be patrolled by starships. Instead, the ancient Greeks had it right when they thought of space as a unique realm, one that is altogether different from the terrestrial sphere.

As a realm, space is implacably hostile to humans. Therefore, the cost of sending humans into space and keeping them there is enormous, with the ultimate return on investment questionable, even negative. As Alex Roland notes in a provocative paper that concludes this volume, efforts to create and station “space warriors” in earth orbit would be analogous to producing a new breed of ICBM silo-sitters, the difference being that these space warriors “will cost ten times as much and they will be sitting ducks [for enemy attack] instead of secure moles.” (221) The most sensible and cost-effective way to safeguard critical space assets is not by militarizing and weaponizing space, Roland argues, but by seeking political solutions with rivals such as Russia and China.

Taking the polar opposite view is Everett C. Dolman, identified in this volume as “Air University’s first space theorist.”[1] For Dolman, the U.S. must be prepared, physically and doctrinally, “to project violence from and into space.” Command of space means building weapons suited for space and its active exploitation, a position he supports by citing Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theories on control of the seas. Dolman even argues that other nations’ fear “of a space-dominant American military will subside over time.” A hegemonic U.S. would be a pacific U.S., Dolman suggests, leading to a world that would be “less threatened by the specter of a future American empire.” (124)

One wonders whether Russia or China would be so sanguine as to cede complete space supremacy to a hegemonic U.S. empire. But Dolman is unworried; instead, he implores the U.S. to seize the “high ground” of low Earth orbit while it is still (mostly) uncontested.

Yet is it not more likely that aggressive moves by the U.S. to dominate space will only generate countermoves by rivals, leading to an arms race in space? In his insightful Harmon Memorial Lecture that kicks off this volume, Roger Launius identifies a growing bellicosity in recent U.S. space policy.[2] Since 1995, he notes, the U.S. “has been blocking a movement at the United Nations for an official prohibition of weapons in space despite its widespread support in other quarters.” (15) Effective exploitation of space during the Cold War, Launius notes, “rested on a doctrine of sanctuary, a disallowance of weapons in space, and the right of all nations to use it [space] without interference. From Eisenhower to President Jimmy Carter, this was an inviolate approach.” (19) But a more aggressive stance came with Ronald Reagan and the Strategic Defense Initiative (“Star Wars”) in the early 1980s, in the context of renewed Cold War competition.

Yet, even with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S. military continued to insist on options to “weaponize” space. The reasons for this are not explicitly explored by this volume but can be read between the lines. One is interservice, and even intraservice, rivalry in the context of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Military-Industrial Complex. The Air Force has fought a long battle with the U.S. Navy and Army for control of space, a battle the self-styled “Aerospace Force” has largely won.[3] It involved the hyping of the space mission as uniquely efficacious for global power projection.

Even as this battle was being fought, another one was in progress, and is arguably still being contested, within the Air Force itself, as shown in David Spires’ contribution to this volume. Space visionaries within the Air Force always took second fiddle, first to the dominance exercised by Strategic Air Command (SAC) bomber pilots, and later to the dominance exerted by Air Combat Command (ACC) fighter pilots. To compensate for their second-class status, space specialists within the Air Force came to see themselves as a new cadre of Billy Mitchell’s, a visionary yet misunderstood minority at the mercy of a hidebound old-guard. Intra-service competition amplified by feelings of persecution bred hyper-aggressiveness and the concomitant tendency to over-sell an idea, including, in this case, the need to dominate and even to weaponize space to defend and advance vital national interests.[4]

The American military’s need “to harness the heavens” is surely also a byproduct of our cultural fascination with technology and its putative virtues, such as precision, control, even a god-like vision of the world (incorporated in DoD efforts to gain “total information awareness” for commanders, and shown with deceptive clarity in recent Hollywood movies like Eagle Eye and Body of Lies). A more critical discussion of America’s love affair with technology and space, including the U.S. military’s almost psycho-sexual desire always to be on top – always to “dominate” the high ground – would have enhanced this volume.

It has become something of a truism that U.S. efforts to secure and exercise “global reach, global power” are ultimately enabled by U.S. space power. Both today and in the future, what that may mean is that those on the receiving end of American power will naturally see U.S. space dominance as something other than benign – indeed, as something to be challenged and overthrown.

*The book being reviewed here was “Harnessing the Heavens: National Defense through Space,” edited by Paul Gillespie and Grant Weller, published in 2008.

[1] We still await a Jomini, a Clausewitz, or a Douhet of military space theory. The best repository for current Air Force thinking on space is the Air & Space Power Journal (http://www.airpower.au.af.mil/); the summer of 2004 and 2006 issues of this journal were specifically devoted to space.

[2] The keynote address at these symposia is known as “The Harmon Memorial Lecture” (the Harmon is also given in years which lack symposia). The first thirty Harmon lectures are available in The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History, 1959-1987, ed. Harry R. Borowski (Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1988). All extant Harmon lectures are also available on-line at http://www.usafa.af.mil/df/dfh/harmonmemorial.cfm.

[3] Within the Air Force, the idea of an “aerospace” force dates back to 1958, if not earlier.

[4] In the mid-1980s, the author served in A.F. Space Command, witnessing this attitude at first-hand. The author also wishes to note that he served at USAFA for six years and worked on three Military History symposia (1990; 1998; 2002).