A year ago, I urged readers to forget about President Bush’s “Road Map to Peace” – on which so much attention was wasted at the time, by now a dead letter – and concentrate on the real map of Palestine, radically changed by the construction of Israel’s Apartheid Wall, which was virtually ignored by the international media. A year has passed, and the silence has been broken: thanks to the work of several conscientious journalists, thanks to Palestinian efforts culminating in referring the Wall to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which is due to decide on its legality soon, and – last but not least – thanks to thousands of Palestinian, Israeli and international activists, of Ta’ayush, Gush Shalom and many other groups, whose daily non-violent demonstrations are dispersed with ruthless brutality by the Israeli army. The Wall is now on the agenda, and it should be. But is it a Wall at all?

Disputed Terms

The term has been disputed from the outset: “the Apartheid Wall” is the Palestinian name for what official Israel calls “Separation Fence” of “Security Fence”. I preferred the Palestinian term: a fence sounded like a ludicrous euphemism for 8 meter (26 ft.) high concrete walls with a 100 meter (328 ft.) wide “security strip” just to start with. At present, the surveillance arsenal includes not only patrols and cameras, but even remote-control machine guns are being developed, which, as the Israeli media proudly report, will enable gentle female soldiers to shoot at “suspicious movements” (i.e. human beings) from behind a monitor in an air-conditioned office miles away. For the industry of killing, the sky is the limit.

In fact, both terms – Fence and Wall – are misleading. Even though most people know by now that the Wall is not constructed along the Green Line, but deep in Palestinian territory, de facto annexing to Israel a great part of it (one-third?), both Fence and Wall suggest some kind of contiguous line with the Palestinians on one side and the Israelis on the other. “We over here, they over there,” as Barak’s election slogan went. But is this what’s going on? Not quite. Reality is far more horrible.

What the Wall Really Is

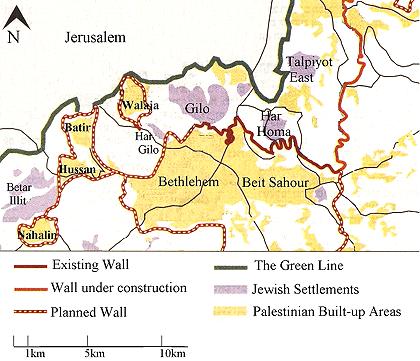

Have a look at the following map, adapted from Amira Hass’ recent article (Ha’aretz, June 25, 2004). It shows just a small detail of the Wall, in the so-called Christian Triangle south of Jerusalem.

The red lines are the Wall – in part already constructed, in part under construction, in part to be constructed. Now have a look at the four Palestinian villages on the left: Nahalin, Hussan, Batir, Walaja. On which side of the Wall are they? Obviously, a wrong question. They are actually encircled by the Wall, trapped by it all around. Batir and Hussan together, Nahalin and Walaja each on its own. Consider the scale: crossing any of the enclaves, from wall to wall, would take 10-20 minutes walking. Any inhabitant of these villages is never more than a kilometer (0.6 mi.) away from the wall. Not only agricultural land, but schools, hospitals, clinics, markets, shops, work, not to mention recreation, are all outside. To get out, you have to pass through a gate, through an Israeli army checkpoint. The gate is probably closed – because it’s open just a couple of hours a day, or because someone up there declared a state of high alert, or because of a Jewish holiday, or because the soldier in charge didn’t get up on time. And if the gate happens to be open, the soldier might let you pass (if you have got the necessary permits), or not (for whatever reason, or for no reason), or ask you for something in return: a small gift, or cursing Mohammad, Jesus or Arafat, or maybe a tip on your neighbor or brother. If your work, or your health, or your child’s life depends on getting out, you’d do anything. Same if you want to get into the village – as guest, truck driver, electrician, or doctor.

There are dozens and scores of villages encircled like this all over the West Bank. Danny Rubinstein reports on some 200,000 Palestinians living north of Jerusalem, many of them holding Israeli identity cards, all totally dependent on the city for schools, hospitals and jobs, all having to get to it through the single filthy, overcrowded checkpoint of Calandia:

“The residents of these neighborhoods have also been informed of the further construction of internal fences that will provide passage into the settlements. These fences, the second phase of the separation fence project, will create five large islands in which the Palestinian populace will concentrate in quasi-ghettos.”

(Ha’aretz, June 27, 2004)

Sometimes houses are fenced individually: Israel’s TV Channel2 (June 25, 2004) recently reported of two houses on the edge of a Palestinian village, around which a Jewish settlement has grown. The two families have therefore been encircled by “their own” fence, separating them on three sides from the Jewish settlement, and on the fourth side from the rest of their own (encircled) village.

So this is no exception: it is the rule. All Palestinians should end up locked in such fences; the lucky ones might enjoy a somewhat larger cage. The location of the walls follows the standard Israeli rule-of-thumb: minimum land for the Palestinians, maximum for the Jews. The walls are constructed just meters away from the last houses of the village, but in many cases, houses are destroyed to make room. Even cultivated fields and water wells are mostly left outside the walls, so they are no longer accessible to their owners. On the map you can actually see how all the open areas are assigned to the Israeli settlements of Gilo, Har Gilo or Betar Illit, whereas the Arab villages and towns have no free inch left.

“Wall” a Misnomer

Now this is neither a Wall nor a Fence. Just like you don’t call a book “a paper,” or bread “flour,” you won’t call this a Wall. What Israel is building in the West Bank is made of walls and fences, but it is not a wall or a fence. It is something very different. I am not sure about its proper name: ghettos? Extra-judicial detention centers? Open-air prisons? A network of cages for humans? I am not sure there is a name for it; I am not sure it has a precedent in human history. Not only has it got nothing to do with the comparatively miniature Berlin Wall, it has clearly very little to do even with the Apartheid Bantustans, which encompassed tens of thousands of square kilometers each. The West Bank cages often comprise just a few hectares, which is a different thing altogether.

Decades ago, a common Israeli argument was that the West Bank and Gaza were too small for a viable Palestinian state. Be that as it may, nobody would claim that a fully built-up 2 x 2 km (1.5 sq. mi.) cage, with no public facilities, no land reserves for housing, no fields, and with a gate guarded by a hostile army, is a viable place to live in. The Israeli authorities know this very well; after all, their own passion for land is insatiable. Their intention is clear: sooner or later, the hopelessly caged population will have to leave simply to escape starvation. This is ethnic cleansing, making life impossible so that the Palestinians are forced out. The nearer we get to the Green Line and to major settlements, the smaller the cages get. These are the areas that Israel wants most, so living conditions should drive away the indigenous Palestinian population there as soon as possible.

Those interested in fair peace in the Middle East should therefore find a proper term for the caging network constructed these days in the West Bank, a term that reflects its true nature, and start a major campaign to explain its significance. It is not separation, but a systematic, intentional destruction of the most basic conditions for human life, which inevitably leads to mass starvation – or ethnic cleansing.