A story is told in southern Xinjiang about the first carpet weaver, a princess named Gulem.

One day, her father, the king of his realm, was hunting in the forest with his court advisors. A little bird flew from branch to branch following the king and singing into his ear. The king demanded that his court advisors decipher the bird’s song, but none of them were able to. Finally, one advisor told the king that only his daughter would be able to understand the bird’s song.

The king called for his daughter and she came and told the king that meaning of the bird’s message was, "A woman can make a man into a slave or a king."

The king, angered by this, married his daughter to a poor woodcutter and told her that if the woodcutter became king, he would believe the bird’s message.

The woodcutter sold his wood in town and also traded it for thread. Gulem then wove the thread into clothes and carpets. Her carpets were so beautiful that the townspeople bought them en masse, making the couple very rich and powerful. Soon, they were made king and queen by the townspeople.

Since then, carpets made by the Uigher people of Xinjiang have been named kilim in her honor.

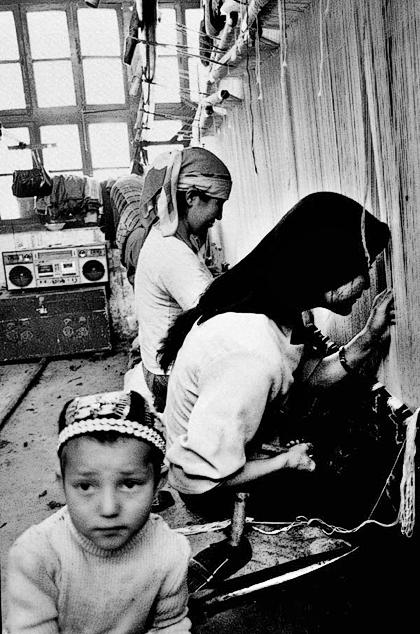

Today, Uigher girls carry on Gulem’s legacy, weaving sheep’s wool into carpets in factories and in their homes. Little princesses as young as five years old begin weaving carpets in Hotan – working after school, on the weekends and during holidays.

The best of these girls also work in the factories, making wool and silk carpets that are sold in the Hotan bazaar, in Kashgar and to tourists from eastern China and abroad.

Villagers in Bazar county, in the desert around Hotan, grow cotton and wheat, but make a mere 1,000RMB per year off of these crops. Umar Nayiz has lived in this county most of his life and his main source of income is in Urumqi, working the coal mines for 100 to 150RMB per day. He has been traveling back and forth from Hotan to Urumqi for 32 years.

Umar Nayiz’s neighbor Abdul supplements his income with the carpets his three daughters weave. His daughters can complete a 2m x 3m carpet in roughly two months. The wool his daughters use is cheap, the colors bright and gaudy and the patterns relatively simple – his family can earn as much as 500RMB per carpet or as little as 200RMB, depending on the buyer and the quality of the carpet. The same carpet at the bazaar is sold for a minimum of 800RMB and up to 1,500RMB.

Girls working in the factories are quick and nimble weavers – the factory carpets are of a higher quality, with more expensive wool and intricate patterns. The factory can produce a 2m x 3m carpet in a little less than two months – for this work, the girls are paid roughly 10RMB per day. The difference lies in the price the factory can get. A wool carpet of this size is sold for a minimum of 1,000RMB and as much as 4,000RMB. A silk carpet – usually 1m x 2m or smaller – starts at 2,000RMB in Hotan.

Antique Hotan carpets sell for as much as $8,500 on the web, but antiques are extremely rare these days. Carpets from the mid-twentieth century sell for as little as $500 and as much as $1,200. These prices are unfathomable to local girls like Pantigul, who works up to 15 hours in a carpet factory at the edge of town for a little more than $1 a day.

"It is difficult to find a good carpet in Hotan," said a traveling carpet collector from Austria. "The vast majority of the carpets you see in the bazaar are machine made and I won’t buy a hand-woven carpet from anyone but the people who wove it – I cannot stand the exploitation."

Hotan carpets are known for their medallion designs and pomegranate trees – also for their lively colors. Carpets made in the factories today do carry these characteristics, but the introduction of cheap, pastel wool has reduced the demand among collectors. To remedy this, some factories are selling rejects from 50 years ago at rock bottom prices and copying designs from Bokhara, Heart and Kazakh carpets from Armenia.

China’s tourism industry is busy promoting Hotan’s jade, silk and carpet industries, continuously referring to 2,000 years of history and to the exquisite quality of Hotan’s products.

But the rivers that for centuries yielded priceless jades have been squeezed dry – most pieces pulled from the Karkashar and Yurongkash Rivers are tiny white jades or dark green jades of no more than 100kg – far less than the 5,300kg piece that sits in the Beijing palace museum.

Ali, a Kashgar native, has started his own fledgling carpet business after learning that foreigners are willing to pay a premium for beautiful, high quality hand-woven carpets. Ali wanders through the bazaar introducing himself to foreigners and bringing them back to his home to look at his carpets. He has an inventory of carpets from all over Central Asia as well as local Hotan and Kashgar carpets. His cheapest carpet sells for 1,200RMB and his most expensive for 4,000RMB.

"I make a few hundred RMB per carpet," said Ali. "After I sell five or six I send money to my friends in Uzbekistan who help me buy more carpets."

The carpet and jade industries have provided for the locals for centuries, and tourists from China’s east coast and abroad still browse the bazaars and factories murmuring over the exceptional beauty of the silk carpets and the sheen of a smooth white jade, but for collectors and experts, Hotan’s golden age has passed into history.