Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

A headline on Washington Post story today: ‘Disturbing’ decline in global nuclear security, watchdog says.

Nuclear security risks are rising for the first time in a decade, according to an annual index released Tuesday by the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a Washington-based watchdog nonprofit that looks beyond the well-known nuclear threats such as weapons proliferation, and toward less widely considered problems, such as the storage of weapons-usable uranium that could be exploited by terrorist groups or the safety of nuclear sites during conflicts. “This diminishing commitment to reducing nuclear risks is deeply disturbing.”

But they say release of “Oppenheimer” might spark positive actions.

Coming later today, my op-ed at the Los Angeles Times, kind of a survey of the (only) three Hollywood movies that preceded the new Nolan epic. Of course, one of them is the subject of my book with same title “The Beginning or the End.” And here are my other pieces this week at Mother Jones (on how Oppenheimer caved and aided that horrid MGM movie in 1946) and LitHub (on the rival film scripted by Ayn Rand).

Plus, tremendous new interest in my book Atomic Cover-up.

Yes, to answer your question, Oppenheimer did visit Japan even after his name was so closely associated with the atomic strikes in 1945, which killed as many as 180,000 civilians. And he was, amazingly, invited to….Hiroshima. Although “Oppenheimer” does flash forward to the 1960s and Oppie earning some redemption, there’s no mention of this visit.

Oppenheimer had accepted an the invitation by the Japan Committee for Intellectual Interchange (JCII) to deliver a series of lectures in Tokyo and Osaka. At an arrival press conference on September 5, 1960, he was, no surprise, asked by a Japanese reporter “about your feelings in coming to Japan as a man responsible for the development of the bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

In his usual suit and smoking his pipe, he paused and replied, “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history. Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.” He paused, then added: “It isn’t that I don’t feel bad. It is that I don’t feel worse tonight than last night.”

So this was the usual conflicted and confusing Oppenheimer way (captured fairly well by Nolan), hinting at regrets but letting them remain vague, unresolved.

He was also asked, again, no shocker, if he would be visiting Hiroshima. “I would like to,” he replied, “but it is not clear that it will be practical.” Of course, “practical” carried a lot of weight there.

In the following days, Oppenheimer found most Japanese, especially fellow scientists and academics who attended his lectures, eager and happy to see him. Speaking to the press, he said that atomic scientists “have the responsibility to inform and explain what they know publicly, if allowed…Japanese people know that this is a time in human history of profound change and problems. I have the duty and hope to talk and meet your people about our common problems and about the difficulty which confronts us.”

A reporter asked if he believed the world would faced “annihilation” due to scientific progress. Oppenheimer responded, “I share that fear.”

At a September 17 lecture in Osaka (in a hall I visited sixteen years later), he said that nuclear weapons were indeed “a source of terror, but we cannot by any action recreate the world of 20 years ago.”

Near the end of his talk, a student stood up but he was no average youth. Ted Reynolds, 21, was the son of parents who had long lived in Hiroshima where they became internationally famous for protesting nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific. (The “Friendship House” they founded, which I visited, still is very active there.) Young Reynolds was there to offer an invitation from his father to come to Hiroshima—a letter Oppie accepted and apparently kept for the rest of his life. The invite declared that the residents of Hiroshima “bear no animosity toward any individual for the tragedy which overtook them…their only hope is that there will never be another Hiroshima….We can understand the delicacy of the situation, but I do hope your decision was not dictated by any feeling that you might meet with personal unfriendliness.”

Having spent a few weeks in Hiroshima myself in 1984, I can say that I do not doubt the sincerity of these forgiving words and focus on the future.

Oppenheimer said he would love to “quietly” spend time in Hiroshima—without cameras or press—and perhaps even visit the new Peace Park. He did not make it. His sponsors wanted to avoid any controversy. Oppenheimer would pass away seven years without returning to Japan—and still, when pressed, defending the use of the bomb against two of its large cities (which he helped target).

Every year at this time I trace the final days leading to the first use of the atomic bomb against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, over at my Pressing Issues blog. In this way the fateful, and in my view, tragic decisions made by President Truman, his advisers, and others, can be judged more clearly in “real time.” As some know, this is a subject that I have explored in hundreds of articles, thousands of posts, and in three books, since 1984, including The Beginning or the End, and an award-winning documentary.

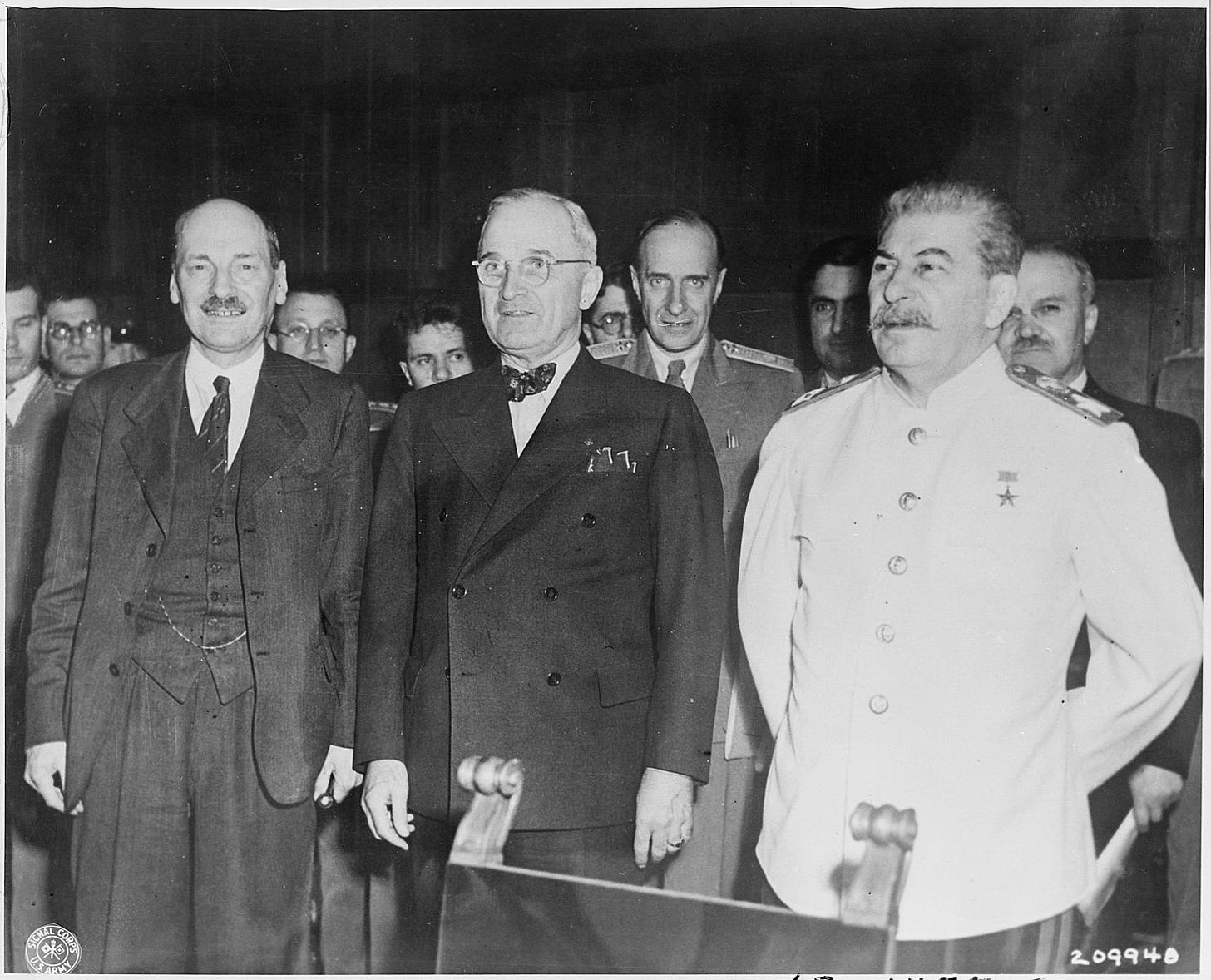

Today’s entry, going back to July 18-19, 1945.

*

At Potsdam, Truman wrote in his diary today:

“P.M. [Churchil] & I ate alone. Discussed Manhattan (it is a success). Decided to tell Stalin about it. Stalin had told P.M. of telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace. Stalin also read his answer to me. It was satisfactory. Believe the Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will when Manhattan [reference to Manhattan Project] appears over their homeland. I shall inform about it at an opportune time.”

So there is a “telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace.” Of course, we’ll never know if peace could have been worked out shortly. One hang-up was that the U.S. was demanding “conditional surrender” while the Japanese wanted to be able to keep their emperor as a figurehead. Of course, after we dropped the bomb, we allowed this condition. This, and Truman’s view that the Soviet entry into the war, set for around August 12, would provoke a surrender made it vital for him–in the view of some historians–to use the new weapon as soon as possible.

Truman also wrote a letter to his wife Bess, affirming his belief that the Soviet declaration of war–even without the Bomb–would cause an end to the war well before the planned U.S. invasion.

I’ve gotten what I came for – Stalin goes to war August 15 with no strings on it… I’ll say that we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed! That is the important thing.

Truman would use the new weapon anyway, a little more than two weeks later—three days before the Soviet attacked Japanese forces—killing at least 50,000 Japanese “kids.”

Thanks for reading Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.

Typo in that the Allies demanded unconditional surrender, and as you note they ended up allowing conditions