Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s substack Between Rock and a Hard Place.

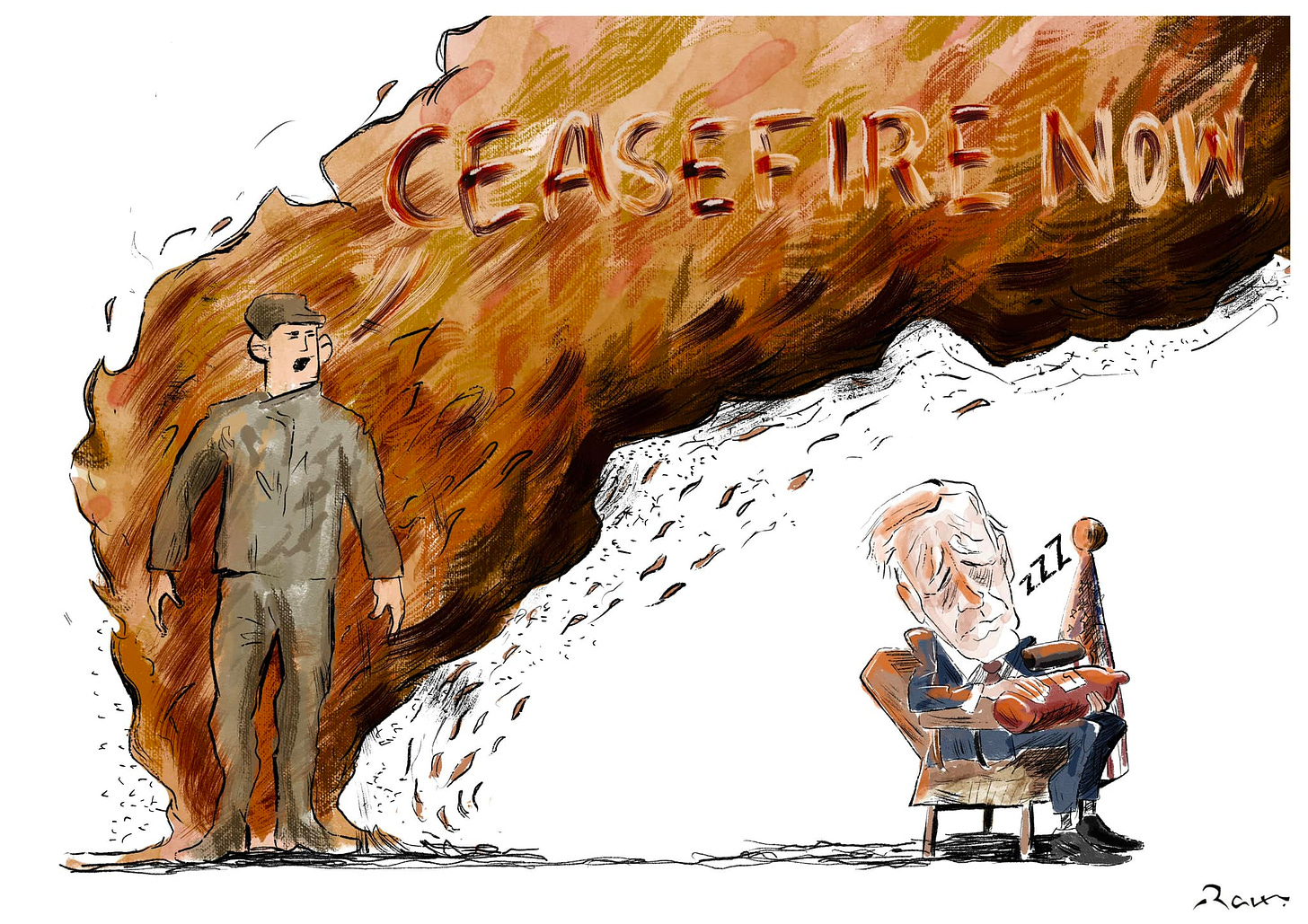

You may have read or heard about yesterday (if you were lucky, as the major media buried the story most of the day) that a senior U.S. airman named Aaron Bushnell, on active duty since 2020, doused himself with a clear liquid outside Israel’s embassy in Washington, D.C., and set himself afire, protesting U.S. support for what he called genocide in Gaza. “I will no longer be complicit in genocide,” he said into his phone. He died chanting “Free Palestine.” He also filmed the act on his phone, and excerpts or still images spread over social media. Memorial gatherings took place last night and are scheduled today in several cities here and abroad.

Among other feelings, this caused me to reflect on the self-immolation of Norman Morrison, a Quaker, in November, 1965, just under the window of Pentagon chief Robert McNamara, to protest the U.S. killing of so many civilians (particularly children) in Vietnam. It came at a time when the great antiwar movement in the U.S., which I soon joined, had not yet gained steam. When McNamara died in 2009, I wrote about it for Huffington Post, so I thought I’d reprint it, below.

Two of the most dramatic, and symbolic, incidents in the long life of Robert McNamara omitted from most of his obits this week were connected to citizen protest of wildly varying types. Yesterday I wrote here about a young artist’s attempt to heave the former Defense chief over the side of a ferry boat. Today: the case of Norman Morrison, a 31-year-old Quaker from Baltimore who, in 1965, handed his infant daughter off to a bystander, doused himself with kerosene and set himself ablaze under McNamara’s window at the Pentagon.

One week later, another antiwar protester, Roger LaPorte, did the same thing in front of the United Nations building in New York. When asked why he had burned himself, LaPorte calmly replied, “I’m a Catholic Worker. I’m against war, all wars. I did this as a religious action.” In South Vietnam, Buddhist monks had been immolating themselves for two years.

Morrison had been particularly saddened by the burning of villages and killing of civilians in Vietnam. Now the U.S. was making use of body-burning napalm, spewed by our aircraft. A Catholic priest’s account of a bombing in a Vietnamese village particularly distressed him. Morrison had resisted taxes, demonstrated, and lobbied in Washington, but now said to his wife, Anne,”It’s not enough. What can be done to stop this war?”

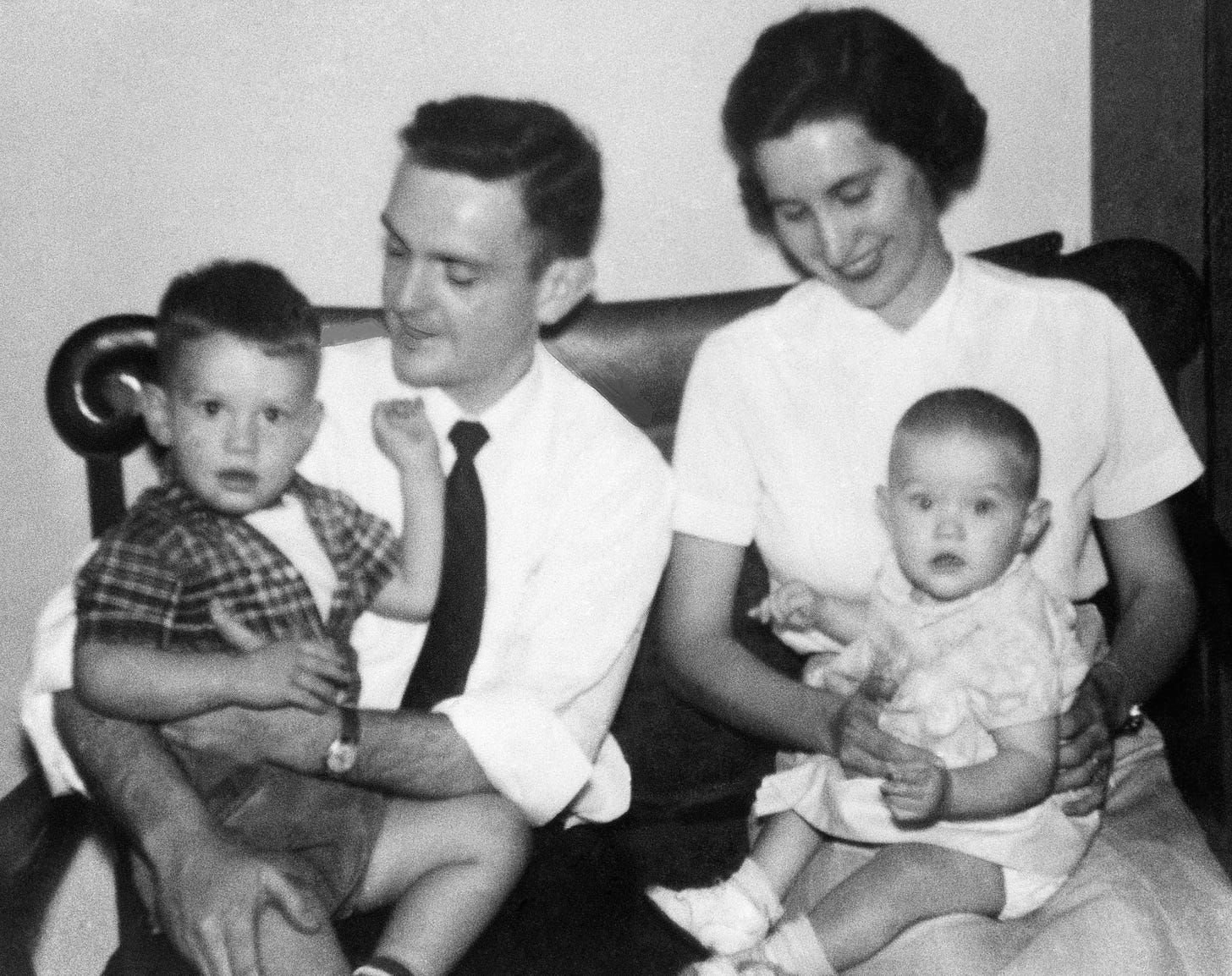

In his final letter to his wife (they had three children), he wrote, “Know that I love thee, but I must go to help the children of the priest’s village.” It is believed that he carried his daughter to the Pentagon that day to remind him of the children he was trying to save in Vietnam.

McNamara would later describe Morrison’s death as “a tragedy not only for his family but also for me and the country. It was an outcry against the killing that was destroying the lives of so many Vietnamese and American youth.”

Morrison became a kind of folk hero in U.S. antiwar circles, his name or face carried on antiwar posters for years. The North Vietnam named a street after him and issued a stamp in his honor – the possession of which was declared illegal in the U.S. Morrison’s widow visited Vietnam in 1999 and met a poet who had written a tribute to her husband. On a visit to this country in 2007, Nguyen Minh Triet, the country’s leader, read the poem near the site where Morrison set himself ablaze.

McNamara would devote two pages in his memoir, In Retrospect, to Morrison’s death. Morrison’s widow wrote to McNamara, thanking him for at least making a partial public apology about his role in the Vietnam War. He then called her to thank her. In an interview, she said, “Norman’s death is a wound that we’ve both carried. In an odd twist of fate, we have come into a kind of communion with each other. We are both victims of the war.”

But others criticized McNamara for exploiting her letter and running part of it in an ad for his book.

Paul Hendrickson, the former Washington Post reporter and author, wrote at length about the Morrison self-immolation in his book, The Living and the Dead. Here is what he told Brian Lamb on C-Span in a 1996 appearance.

Anne Morrison Welsh is her full name now because she remarried, is a deeply forgiving woman, a deeply Christian woman and has taught me personally a lot about the nature of forgiveness. I end this book going back to Anne Morrison and her message to me is, “Let vengeance be for the vengeful.” But to answer your question, directly, when Mr. McNamara, sitting in this chair, came out with his book a year ago, “In Retrospect,” that book provoked instant kind of outrage in America, Anne Morrison Welsh’s response – was otherwise.

Her response was to salute it in terms of, “Well, this perhaps will help us in the healing process.” And she wrote a beautiful letter and released it as a statement. And, unfortunately, I have to sit here and tell you that I felt that that letter was exploited by Mr. McNamara. Well, very shortly after it appeared in a full page ad for his book, he was handing it out to reporters in Washington.

Morrison’s daughter Christina, after traveling to Vietnam, would observe, “As a child, the only thing that helped me understand my dad’s death was being aware of the suffering in Vietnam. On our visit, I got to meet some of those children who told us how much my father’s sacrifice meant to them. This was indescribably healing for me.”

Steve Earle, “Jerusalem.”

Thanks for reading Between Rock and a Hard Place! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood and at his substack Between Rock and a Hard Place.

It’s a good article. Unfortunately, that won’t stop wars from occurring and won’t stop them from recurring. People setting themselves on fire will make themselves martyrs to their supporters.

I wish they would find another way to protest, I wouldn’t even want to see someone doing that to themselves.