Reprinted with permission from Greg Mitchell’s newsletter Between Rock and a Hard Place.

Was great to see CNN’s Dana Bash trending on Twitter yesterday. Uh, what? Well, it transpired because thousands were bashing her (ahem) after she compared threats to Jews in the U.S. this week to dangers for them in Europe in the 1930s. She later claimed that anti-semitism is “raging across the U.S.” Joe Scarborough this morning called his MSNBC viewers “too stupid to see” that the protests were hurting Biden’s re-election prospects.

The most striking example of violence, however, took place at UCLA this week with about 200 counter-protestors attacking a pro-Palestine encampment (filled, as it happens, with many Jewish students) with fireworks and other objects, injuring about twenty-five as police stood by. Police were then ordered to clear the encampment early this morning, with dozens of arrests.

The college protests and encampments, and police actions and media hysteria, have obviously reached a boiling point.

Of course, this makes me recall my first college sit-in 56 years ago this month: a group of maybe two dozen of us blocking the doors of our administration building (from the outside). My main contribution was hauling my tape deck from the dorm, along with an armful of reel-to-reels – new Hendrix, Stones, Dylan etc. – and talking an unarmed Burns guard into letting me plug in the cord inside the door! So, for example:

Obviously not a very menacing atmosphere but in truth we could have all been expelled from our small, conservative college in a heartbeat. Some of our fellow students came by in the middle of the night to toss buckets of water on us. Still, it ended peacefully after a couple of days with no arrests.

Later that month, when an Army general came for his annual inspection of ROTC troops, we staged a kind of die-in. Again, no strong repercussions. I was elected as one of five leaders of a new group, to counter the Student Senate, called the Free Student Union. But the school president banned our small SDS chapter (I was not a member) from campus, which made national news. The college had earlier canceled a speech by Allen Ginsberg but after our protest a new Open Speaker Board (with faculty and students dominating) re-invited him and he appeared before a large crowd.

A year later, another sit-in, and the year after that, a campus strike after Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia and Kent State. Then, the year after I left: Some kids burned down the ROTC building. I kid you not. I don’t know if they ever IDed the perps or what happened to them if they did.

Anyway, back to the present. In the past week we’ve seen a score of major articles or cable TV hits on the theme of how the student protests, allegedly unpopular with voters, might cost Biden re-election in November and bring us Trump II. This will, some say, reach its climax this summer because guess where the Dems will be convening this August for their national meeting… yes, they will be back in… Chicago. Protests guaranteed. Of course many polls also show that Biden’s militantly pro-Israel policy in the Gaza war is opposed by a majority of Democrats of all ages. So who knows.

I’ve been there before, one might say.

Still in college, and still in 1968, the first major political event that I covered s a journalist, or even attended (many antiwar marches in D.C. were to come) arrived. Yes, it was the infamous Democratic convention in Chicago, when the conflict in the streets, and on the convention floor, turned bloody.

I never made it inside the convention hall – but I did grab a front row seat for what “went down” in the streets, as we used to say.

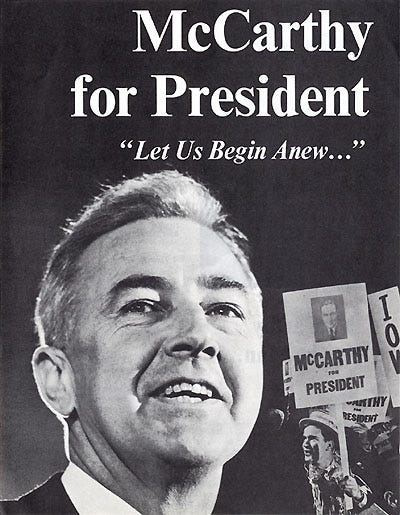

The week culminated on the night of August 28, 1968, in the crushing of Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s anti-Vietnam crusade inside the convention hall and the cracking of peacenik skulls by Mayor Richard Daley’s police in the streets. Together, this doomed Hubert Humphrey to defeat in November at the hands of Richard Nixon, as many liberal/lefty voters stayed home. McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy – do we have to call him RFK Sr. now? – had gained most of the votes during the primaries, but HHH still got the nod at the convention.

I’d been a political campaign junkie all my life. At the age of eight, I paraded in front of my boyhood home in Niagara Falls, N.Y., waving an “I Like Ike” sign, and in 1960 took Nixon’s side in a big school debate (I lost that vote, 22-3). In 1968 I got to cover my first presidential campaign when one of McCarthy’s nephews came to town, before the state primary, and I interviewed him for the Niagara Falls Gazette, where I worked as a summer reporter during college. I had been chairman of the McCarthy campaign at my school and lived and died with his campaign that spring.

My Chicago assignment for the Gazette: I was to hang out with the young McCarthyites and the anti-war protesters. To get to Chicago I took my first ride on a jetliner.

To make a long story short: After two nights of observing but not joining skirmishes in the streets, on the climactic night of August 28, 1968, I ended up a dozen floors from ground level at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in downtown Chicago. I was in McCarthy headquarters watching the antiwar plank get voted down by the Dems, as reporters got pushed around by cops on the convention floor. Then McCarthy (and George McGovern, who had carried the ball for the forces of the assassinated Robert F. Kennedy) got ready for his inevitable rejection at the hands of the delegates. I might be in this photo of McCarthy headquarters that night:

Suddenly the TV screens were filled with images of protesters getting beaten up near a major intersection on Michigan Avenue near Grant Park. Almost as one, in a surreal moment, we realized that, hey, that was just a few dozen yards directly below us. With the windows on the street side of the huge room tightly closed we couldn’t hear the screams or even smell the tear gas – that is, until we pulled back the curtains and cracked open the glass.

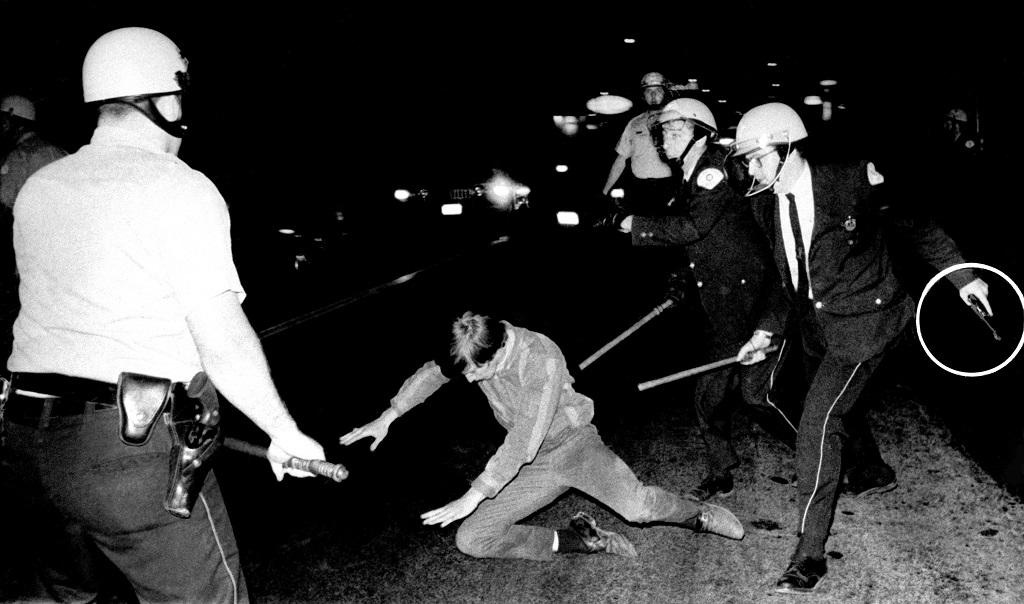

Then we could see police savagely attacking protesters with nightsticks at the intersection directly below. What would later be labeled a “police riot” by a federal panel was in full swing, so to speak.

Within minutes, I screwed up my courage and headed for the streets. By that time, the peak violence had passed, but cops were still pushing reporters and other innocent bystanders through plate glass windows at the front of the hotel. I held back a bit in the lobby, where someone had set off a stink bomb.

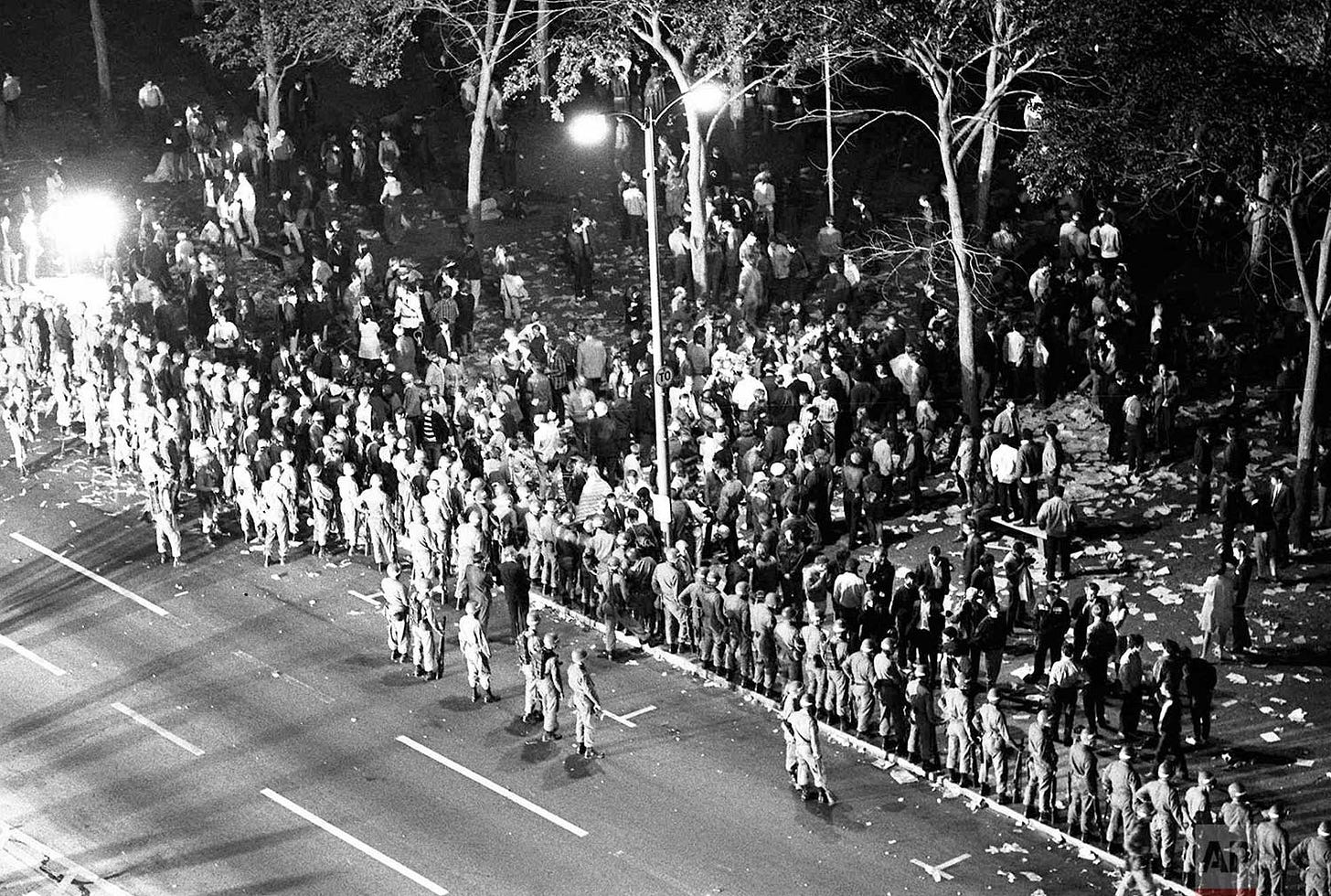

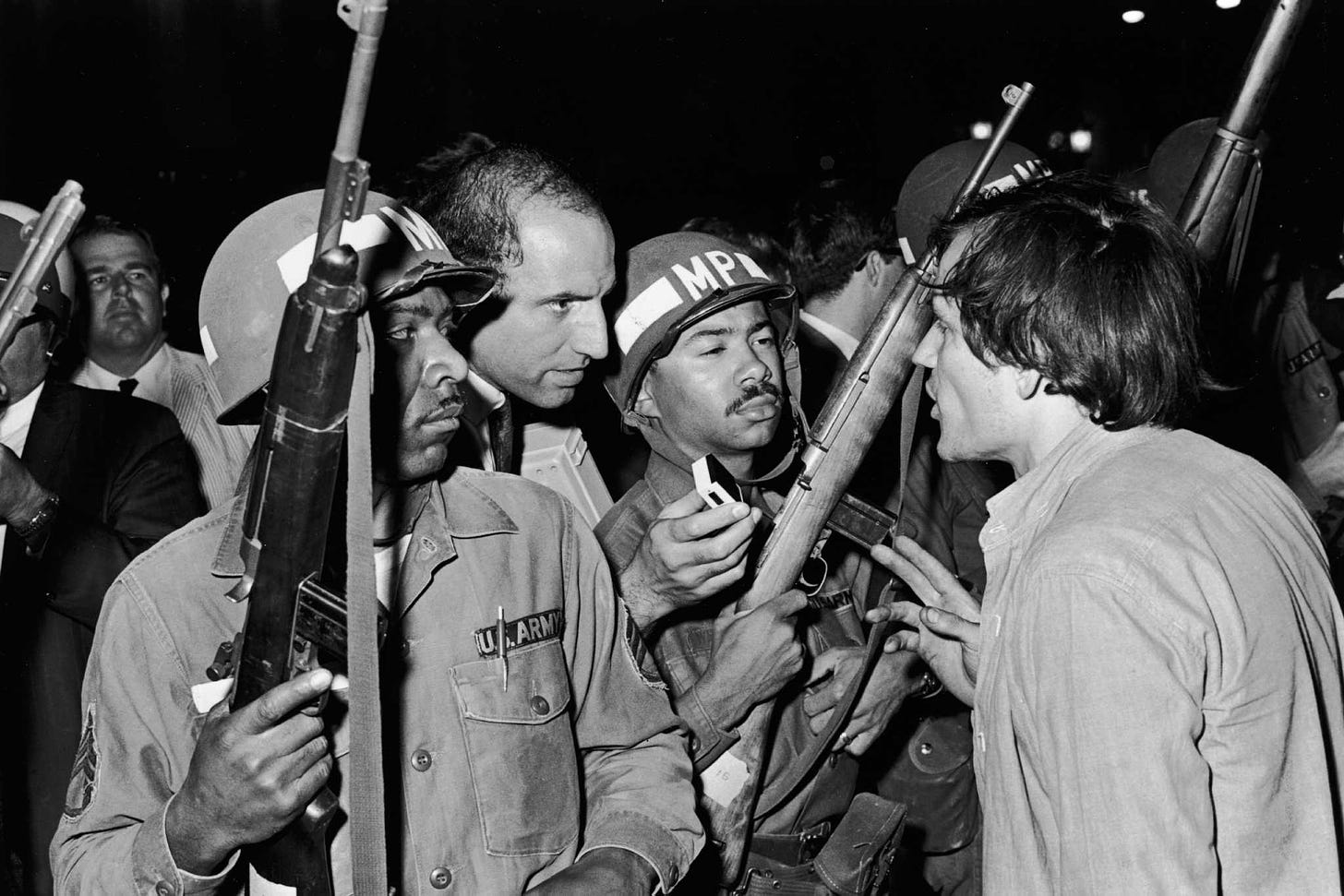

Finally, I crossed to Grant Park where the angry protest crowd gathered, with armed soldiers and jeeps covered with barb wire and mounted with machines guns formed a line along the street. We feared they could move forward and try to push out of the park at any moment (and many were ready to resist). Yet there I stayed all night, as the crowd and angry chants directed at the cops increased.

Many in the crowd wore bandages and had fresh blood on their faces. Phil Ochs arrived and sang, along with other notables, including some of the peacenik delegates, plus Dick Gregory, Norman Mailer and other celebs. I might be in this shot:

But not brave enough to do this:

In the morning some of the protesters filled the lobby of the Hilton, and when delegates exited for the final day of the shattered convention, we chanted, “You killed the party! You killed the party!” The next night, police raided McCarthy headquarters upstairs and arrested a bunch of people.

When I returned to Niagara Falls that Friday, I wrote a column for that Sunday’s paper. I described the eerie feeling of sitting in Grant Park, thousands around me yelling at the soldiers and the media, “The whole world is watching!” – and knowing that, for once, in my young life, it was true.

A few years later, I interviewed McCarthy in New York for a major profile for Crawdaddy – he was running for president again, mainly because he could, but he seemed sadly dispirited. In his New York Times obituary this week he was quoted saying that he never could forget the smell of tear gas in the lobby of the Hilton in Chicago in 1968. I guess I haven’t either.

Later I would write two books for Random House about controversial American political races: “The Campaign of the Century,” exploring Upton Sinclair’s race for governor of California in 1934 and the birth of modern politics (winner of the Goldsmith Book Prize) and “Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady” on 1950 contest between Richard Nixon and Helen Gahagan Douglas (a New York Times Notable Book for 1998).

Duane Eddy, one of the great early rock ‘n roll guitarists, has died at 86. He had a lot of hits but he was mainly known as inventor/populizer of “twang” and influence on many who followed. One of his 1959 classics:

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent award-winning The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood – and America – Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years. He writes often at Oppenheimer: From Hiroshima to Hollywood.